The Boston Globe

March 14, 2003

"Full House: The sounds of Empty House Cooperative have gone from a Central Square living room to the ART's world premiere of 'Highway Ulysses'"

By Joan Anderman, photo by Dominic Chavez

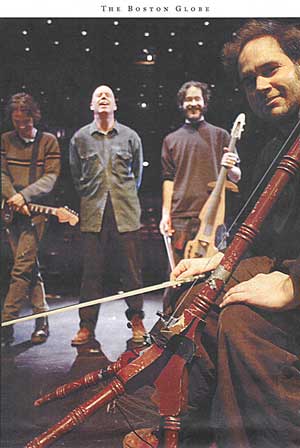

the empty house cooperative with playwright rinde eckert

(left to right: chris, rinde, jonah sacks and david michael curry with his coat rack bass)

Professional opportunities tend to be limited for experimental music collectives that have no songs, no rules, and no name for what they play. Boston's Empty House Cooperative - just such an ensemble - has found work on the metaphorical edges of the dial. The group has performed live accompaniment for silent-film screenings, provided the ambient score to a marathon seven-hour reading of "Big Sur" at a Jack Kerouac festival in Lowell, and improvised dinner music at the Middle East bakery in Cambridge.

"It was sort of subversive," says Empty House founder and de facto music director David Curry of the restaurant gig, "because people didn't know they were listening to it."

Curry's is not the sort of nuts-and-bolts attitude that fuels more conventional music careers. But it's exactly the kind of outsider perspective that landed Empty House Cooperative its current plum of a job: co-creating and performing the music for the world premiere production of Rinde Eckert's "Highway Ulysses," which runs through March 22 at the American Repertory Theatre's Loeb Drama Center.

Eckert was in the early stages of conceiving his musical/theatrical contemporization of "The Odyssey" - which follows a war veteran on a cross-country journey to find his son - when he first heard the Empty House Cooperative. Like many remarkable collaborations, this one began with an act of serendipity. In the spring of 2001, ART subscriber Leslie Brokaw, a local writer (and a contributor to this newspaper) and the sister of Empty House member Chris Brokaw, sent a tape to ART artistic director Robert Woodruff. Woodruff flipped over it and played it for Eckert, a friend and colleague.

"'This is the sound,' I said. 'This is the sound,'" recalls Eckert of hearing Empty House's music. "There was an unusual timbre, a sense of openness. Something that sounded contemporary and ancient, out of the ordinary but accessible. We got together a couple of times, and there was a brightness in the room. Once I met them, I didn't have much doubt."

Neither did the three core members of Empty House (which has a fluid lineup of as many as a dozen players), despite that their collective theater experience amounted to guitarist Chris Brokaw's appearance in "West Side Story" at his high school in Scarsdale, N.Y.

Curry is best known for his involvement with sonic adventurers the Boxhead Ensemble and local folk-noir outfit Willard Grant Conspiracy. In "Highway Ulysses" he plays viola, theremin, horns, homemade instruments, singing saw, and digital loop samples. Brokaw, a fixture on the Boston rock scene, was a member of the slow-core band Codeine and indie rockers Come, and now splits his time among Consonant, Empty House, and his solo project.

Cellist Jonah Sacks (who moved to New York last year) and Eckert's musical director - keyboardist Peter Foley - round out a quartet that redefines the notion of a pit band.

"It's a strange blend of thinking, of paying attention and being on the ball, and being ourselves," says Curry. "Rinde is very intuitive, and very welcoming of other people's ideas. As the play was being developed, he was always looking for textures and elements that fit with his ideas. We would bring lots of instruments, and as we went along, we'd figure out what worked. In the show, beginnings and endings are well rehearsed, but not every musical gesture is planned."

In other words, there's room for improvisation in the score to "Highway Ulysses" - which involves a delicate balance of detailed composition and free-form musicality that exists, in part, because Eckert stumbled upon a group that was up to both the technical and aesthetic challenge.

"I've never had the luxury of - well, I've never had them," Eckert explains. "I had the benefit of their knowledge of one another."

That synchronicity outweighed such potential concerns as the fact that Curry doesn't read music. Where Sacks, a schooled musician, is a seasoned sight reader and Brokaw follows guitar tablature, Curry draws color-coded symbols and little pictures of his viola fingerboard in his copy of the script, which doubles as his score.

"Plenty of people who read music don't have the sensitivity these guys have," says Eckert. "I'm less concerned with musical integrity than theatrical integrity. When I started composing, it was from an academic point of view, with these theoretical pretensions based in the notion of the Greek pentatonic scale. Then it devolved into whatever works. Theory is great, but it doesn't get the job done. The piece demands that things just happen."

The move from Curry's Central Square living room - where Empty House began in 1997 as a series of Sunday brunches - to the hallowed halls of the ART feels natural to musicians whose mission is to let things just happen.

"Empty House is the most relaxed thing any of us has done," says Brokaw. "There's very little verbal synthesizing of what we're trying to do and no real goals." That may be changing, though, after a taste of the theater life. "My other bands have a bunch of plans," says Brokaw. "But I'm hoping that 'Highway Ulysses' will lead to other work like this."

Joan Anderman can be reached at anderman@globe.com